1930's Germany: Rearmament Over Relief

How The Nazi's Sold Workers a Leisure Mirage and the Incompatibility of Leisure & War

I have been interested in and reading quite a bit of economic history lately, a subject I have precisely zero authority on. And no work has made my ignorance more clear than Adam Tooze’s excellent book, “The Wages of Destruction”. A work where the economics of Nazi era Germany are put on the operating table in such a helpful and straightforward way. My aim here is to take Tooze’s masterclass and see what principles lie within the Nazi policies and civilian overwork that can help us move closer to leisure and liberation.

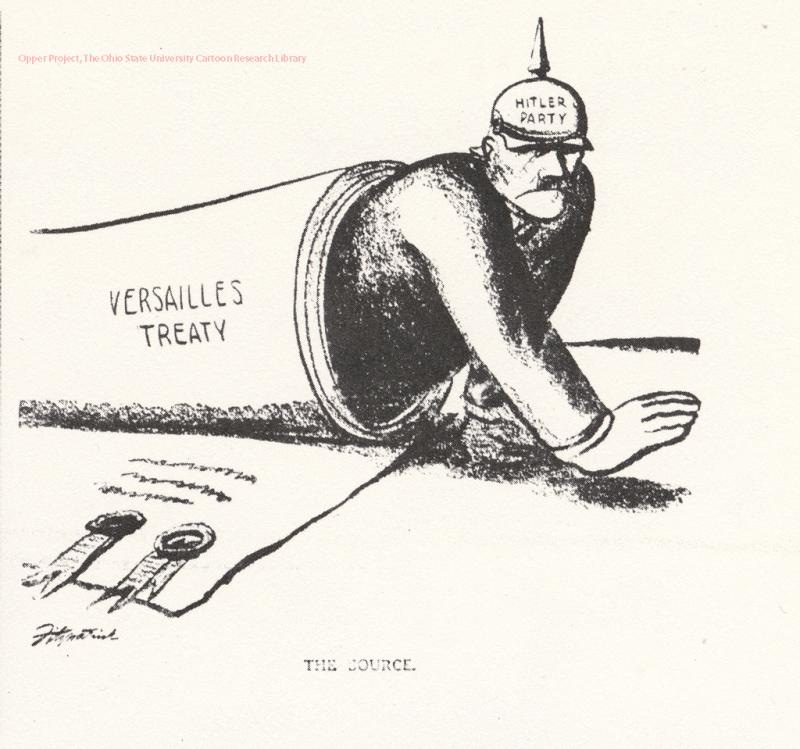

To set the stage, the German economy in the late 1920’s was crippled by the Great Depression where there were 6 million unemployed and widespread hopelessness and social unrest. This left Germany vulnerable and the Nazi’s, as Nazi’s do, exploited this vulnerability by promising rapid recovery. They seized on this crisis.

Nazi economic policy of the 1930’s was heavily aimed toward rearmament and autarky, the purpose of which, of course, was to prepare the country for total war. This meant a few things, massive state spending in the form of things like public works programs, mass industrialization and tight controls on civilians in the form of wage, price and consumption controls. On the surface, things like public works programs and industrialization don’t sound all that bad, but the public works programs and industrialization efforts of Nazi Germany did not prioritize German consumers, the priority was the German state, namely the state’s military. Under the guise of public work programs there is a facade that looms over Nazi Economic Policy that seems pro-worker and pro-consumer, but in reality is solely in service of the (illegal) over-militarization of the German state.

In order to see this facade at work, the “Kraft durch Freude” program has to be examined, which Tooze does so well. Tooze notes that the KdF was first and foremost a propaganda tool, and only secondly was the KdF a program to organize and promote leisure activities for workers. The thing with the KdF was that it mostly was a showcasing of the regime’s apparent commitment to improving worker’s lives. This being done by offering subsidized vacations, cruises and even trips to the Alps or Baltic Sea. Needless to say these were very popular, and something like 10 million Germans took part in these opportunities annually. Now, you might say, well Mr. Lavitalenta, are vacations, cruise and trips to the Alps not leisurely activities? And to that I say, well… on the surface, yes, but not in this case. Allow me (Adam Tooze) to explain.

The skinny is that these leisure programs were tightly controlled and only served worker’s lives in order to align them with Nazi ideology. They were essentially pay offs. And participation was less about genuine liberation, and more about making German workers feel liberated momentarily. This is not to say the individuals on these trips didn’t enjoy themselves in these activities, we aren’t examining how enjoyable the Alps are here, what we are examining is economic policy.

In short, the reason this was not true leisure is that 1) this was not an honest attempt to empower German workers and 2) these handouts don’t subvert the underlying power structure but in fact reinforced the underlying power structure by giving workers an illusion. And 3) the other reason this was not true leisure is because the KdF did not actually increase the free time of German workers. As Tooze cites, at the apex of German Rearmament, working hours remained long and even increased as efforts intensified by the mid to late 1930’s.

The priority of sending you to the Alps for a few days was to buy loyalty.

What would happen if liberation was a real priority for the German state was resources for consumer goods and domestic infrastructure, things like housing, public amenities, etc., would be implemented and put to use for the average German worker to enjoy. But what happened in reality was that those same material resources that could have been invested back into the public to empower them, were diverted to military spending, diminishing further the social conditions.

There were measures put into place that didn’t help affordability and living standards either, namely strict wage controls. Wage controls that were meant to prevent inflation and ensure that as many resources as possible flowed to rearmament. Tooze even highlights how, even though unemployment fell significantly during this time, the real wages for most Germans declined between 1933 and 1939 because of the price increases and restrictions on wage growth since the Nazi Regime’s focus on military production constrained consumer good industries.

This is a good example (and one we may or may not be seeing today) where war is more of a priority than households, and how all “economic recoveries” are not created equal, since there are “economic recoveries” that happen on paper but the purchasing power does not improve for every day consumers. I believe you could call this a vibecession. The state took care of it’s goals at the cost of the common people.

Nazi Germany was an exploitation machine and whether they knew it or not, those who thought themselves as chosen were also exploited.

Thanks to Adam Tooze and his wonderful work, I now understand that the economic policy of Nazi Germany is inseparable from Nazi ideology and that the two, very intentionally, inform one another. It is well known that the regime goals during this time were a creation of a racially defined Volksgemeinschaft (people’s community) along with territorial expansion with this military juiced to the 9’s they dumped all their resources into. With this in mind, it becomes clear that the economy in Nazy Germany was not intended to be a tool of allocating resources to the people, but it was a mechanism to enforce ideological conformity and how to get its populace to serve its ends, not their own ends. In this way, Nazi economic policy of autarky being a tool of conformity and suppression is virtually identical to austerity being a tool of conformity and suppression.

In order to get the masses to conform ideologically and accumulate more private resources for their military projects, there was what is known as the aryanization of Jewish businesses where wealth and assets were funneled into the hands of Nazi-aligned firms and individuals. Was this economic plunder, yes of course, but it also accomplishes the racial ideology of the regime. What happens when this is the case is that all economic activity gets subordinated to their ideological vision, and because of the autarkic war-driven racist ideology, not only was slave labor racially motivated, as we all know to be the case, but in their mind it was also economically mandatory. It is a strange thing where their fundamentally broken and contemptible view of humanity led them to their stupid policies and their stupid policies led them to their completely contemptible ideologies, it’s a house of cards. Put another way, their reprehensible ideology is inseparable from their nonfunctional economy. It’s all baked in. (I am sure there is someone out there who has written about this extensively and put it much more eloquently than I can. I just don’t know about it, if you do, please let me know)

It seems to me that racism, like autarky, like austerity1, is an MLM scheme.

So if exploitation is a policy decision, that must mean that leisure is a policy decision as well.

I need to define austerity here because Nazi Germany did not engage in austerity in it’s purest form. It was more of a “Spending For Me and Austerity for Thee” sort of deal where there was massive state spending on rearmament (17% of the GDP was military spending by 1938, p.219) So when I say Nazi Germany was austere I am referring to the wage controls and controls on consumer good shortages that created austerity like-conditions for civilians, not so much for the state. Whereas a “pure” austerity also includes the state tightening its belt as well.